nterviewed by Briar Essex (they/them) SAS ’19

Briar: Thank you so much for taking the time and making the trek back to campus!

Tom: You’re welcome!

BRIAR: So, you are an alum of Penn?

TOM: I am yes.

BRIAR: May I ask when you graduated?

TOM: I graduated from my undergraduate in 1966.

BRIAR: Good for you! Do you come back often?

TOM: Yes, pretty often. I love the campus, and I do come here for programming sometimes. I was here more than usual over the past year because of the Whitman at 200. It’s easy, I can walk here. I haven’t been a very good alum. I hadn’t been to a class reunion until my 50th [laughs]…

BRIAR: Well, I feel like that’s one of those things where, when you live in Philadelphia…

TOM: Right. I could have won the prize for the person who traveled the shortest distance. But I really was touched by the reunion and did see people I hadn’t seen in years. And my connection with Penn over the years has been through Mask and Wig.

BRIAR: Sure!

TOM: I was in it as an undergraduate. I was in their shows. I wrote songs for them. Then I had a leave of absence for about 40 years because I came out. I was on the Board, but the chairman of the Board asked me to resign. There had been an article about the opening of a bookstore called Giovanni’s Room. Two friends and I started it in 1973, and the Inquirer ran an article that included our pictures, and it made the old Mask and Wig guys pretty nervous. The attitudes there have changed completely. But at the time, they were very sensitive about being thought to be gay, because the whole humor of the reviews is men dressed as women. Still, they have to be sort of obviously masculine. Non-Binary men had to make fun, dressing as women. But then some years later, a group of undergraduates, 7 openly gay graduates, got in touch with me and asked me to rejoin, which I thought was very sweet. I had to think about it for a while because, you know, it was a sad and nasty moment.

BRIAR: I can’t imagine.

TOM: But then I did come back, and I did begin writing songs for them again, so that’s a nice connection with Penn for me.

BRIAR: I think it’s, in a way, sort of strange for me. I think some of the people you are in Wig, who have heard your story, who would not be surprised because they know the alumni board very well. But for so many people who are in Wig now, it has really changed extraordinarily into something positive.

TOM: Oh, yeah, I would not have gone back [if it had not changed]. When it was started in the late 1800s. 1889 maybe? I can’t remember. It was for white, Mainline, Protestant, boys only, and my father and my uncle both went to Penn. They knew I wanted to be in Mask and Wig, and we are a Jewish family. My father and my uncle said, “don’t get near it because you’re going to be disappointed. They don’t take Jewish kids.” That had already really changed by the 60s. They did take me. I wasn’t the first, too. I was maybe the third. [laughs] Then, over the years has become racially diverse. Gay kids can come out. The only thing that they’re still not acceptable in the Mask and Wig Club is women.

BRIAR: It’s also been interesting to hear people talking about how to navigate that and how to navigate that in a responsive way that does move with the time but also gives credit to Bloomers and the work that they’re doing.

TOM: When Bloomers came on the scene, which was not that many years ago, that kind of gave Mask and Wig a little bit of coverage, you might say. I think a lot of people understand that that’s the history, the culture, of it. Bloomers is all women. Eventually, Mask and Wig will have to deal with a trans person who comes to audition, and we’ll see how they handle that.

BRIAR: I will say that I don’t know many people who are in Wig at pre

sent, but my sense of the people who I know and love will be, like, “all right, it’s 2019. It’ll be 2020 when the next audition cycle happens. Can you sing? Can you tap dance? Great! Let’s go!”

TOM: I think it will be that way. I know so many of the undergrads now, and it’s a good group. Even the straight white guys are not threatened by differences. I think it will be okay.

BRIAR: You said that you were not a very good alumnus, but as I understand it, you were one of the people who were very, very influential in creating the space through donations.

TOM: I would like to say, “yes,” but it’s really not right. I see my name on the plaque on the wall downstairs, and my husband and I did make a contribution, and we knew Bob Schoenberg for many years. I would like to claim responsibility for a lot of things, but not the Carriage House. I was busy with Giovanni’s Room, The Attic Youth Center, the William Way LGBT Community Center. I would take some credit for helping those things along the way, but here? I like this facility, and I’m glad that it has prospered, but I cannot take any claim for being a founder or anything like that.

BRIAR: So then can I ask you about Giovanni’s Room? Because that’s a space that I love. Over the summer, I was in a book group called Reading Queerly, which met and Giovanni’s Room, and it was very cool. You know, did we really talk about anything? No. But we did have really cool moments of collectivity and connection, which was amazing.

TOM: I was really just more or less getting involved in the political– the Gay Liberation movement was so small and new. I think we started Giovanni’s room four years after Stonewall. Actually, in Philadelphia, they were very few venues, very few places where people could go other than gay bars and a couple of bathhouses. Those are fine. The bars are fine. Bathhouses are fine. In general, a laid-back atmosphere didn’t exist. So two friends and I thought that we would start a queer bookstore. The only one that we knew of was the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookstore in New York, which is now gone, but I think it was started in 1967, so a few years before Stonewall.

The owner, Craig Rodwell, was at Stonewall. He was a dynamic leader of the movement early on. He helped us tremendously! He was extremely generous with his time; helped us choose our inventory. We found space on the 200 block of South Street. It was hard to get a realtor to rent to us because there were no protections at that time and because we wanted to tell any realtor or the owner of the property what we were doing– we didn’t want to surprise them– we said, “we’re opening a gay and feminist bookstore.” A lot of our first attempts were met with an owner who didn’t want “that kind of business,” but eventually we found an owner who said, “yes!” We were at 232 South Street, and we were a little nervous about getting a rock through the window or something. That never happened. The neighbors, the people, the businesses down there welcomed us. Sometimes after school, teenage boys would run in the door and giggle and point and laugh and then run out. That’s about the extreme harassment. [laughs]

BRIAR: [Sarcastically] Oh, no! What’s going to happen? [laughs] Nothing. [laughs]

TOM: Right! So, that was the early Giovanni’s Room.

BRIAR: I also think it’s interesting that you and your friends identified a need for spaces that were not bathhouses and bars. Yet, here we are in 2019, and if you go to the gayborhood, you have Giovanni’s Room and Bars. That’s still kind of it. A lot of people of my generation, who are also conscious spaces, acknowledge that this doesn’t leave a lot of spaces open for younger folks who…

TOM: Excuse me for jumping in, but the William Way Community Center and The Attic are a few other places that are safe spaces for young people.

BRIAR: 100%! And I think the programming that goes on in these spaces is phenomenal. Learning about The Attic Youth Center, I went my freshman year, and I hadn’t been connected to many parts of the broader queer culture of any kind and learning about that and thinking, “Wow! That is really cool that this place exists as a distinct specificity. The more that I sort of think about these things, I surprised at how few and far and in-between they are: LGBT centers whose mission is to serve LGBT youth. Philly is doing, well obviously everyone could do more. And you mentioned that you were involved [at The Attic] as well?

TOM: I went as a volunteer, and I was there for about 10 years. I have facilitated music groups and writing groups. The youth could write about anything they wanted. In terms of music, I brought a keyboard with me, and they would play, and we would sing. Some of the young people had guitars. It was great fun. Then I was asked to be on the Board, and I did it, and I regret it because it was more fun devoting time to the youth than to have a lot of meetings! [laughs] But, that’s the way it works. I still have ties with some of the young people. At the Indigo Ball the other night– the William Way fundraiser– there was some Attic youth who are now not youth anymore. It’s always fun to run into them to see what they are up to.

BRIAR: That’s fantastic! One thing that can be so impactful is seeing somebody who is older than you are who are doing cool things, who is filled, who is either like “aggressively normal,” or doing incredibly cool things. Granted, I don’t know you that well, but I was given a link to your website, which says “father of two. An alumnus of Penn.” In 2019 these are more “normal” and doing Oscar visits Walt. I think this is a wonderful combination.

TOM: I’m lucky. I like what I do, and I love the way that we create our own families. I’m fascinated by that, ever since we became involved in our family. I think it’s so creative that we have our own definitions of family. A lot of people are not ready for it, but they’ll have to get used to it.

BRIAR: I think what has been cool to be in the middle of, with my generation, is people being like (A) what the definition of normal is? But also (B) why are we trying to be normal?[laughs] Why do we feel this affinity to ascribe to this?

TOM: “Normal” is only majority behavior. “Abnormal” is somewhat of a bad word, but…but I think abnormal works, too.

BRIAR: I like it, too [laughs] So, you started off in Mask and Wig, and then you went off and did some cool things with theater and music, and now you’re bringing it back to Penn.

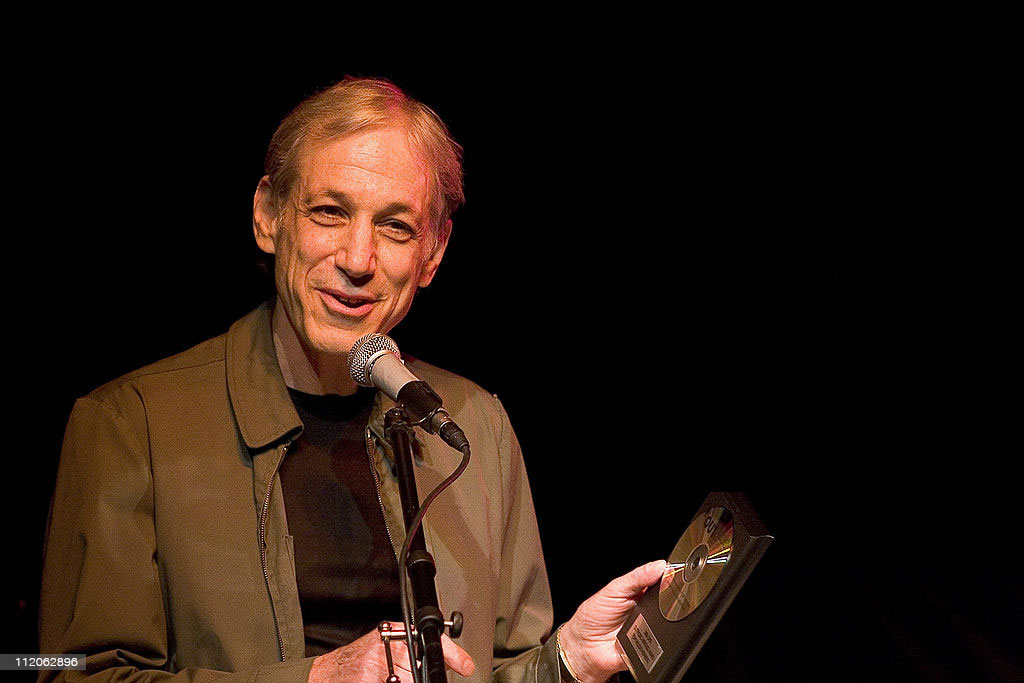

TOM: That’s true. I’m really excited about doing this on the campus. Most of my shows are downtown. William Way is my home base, but I have done shows in many other places as well and in other cities, but for the opportunity to bring a show to my dear old campus? I’m delighted. I hope the word gets out, and a lot of people come: students, staff, and faculty. One thing is that I haven’t really known how to connect with this population. We had three performances downtown, and we were sold out, and we know how to find our audience in Center City. I don’t know if people seem to think that crossing the Schuylkill River is like Crossing into another country.

BRIAR: I agree there are far too many people at Penn who don’t want to cross the Schuylkill River I think this is a wonderful opportunity to look and say, “Hey! It’s not that hard.”

TOM: I had actually been thinking about doing the show with this theme. Some of my recent shows have been cabarets. So, it’s music: some of which I write myself, but we were also singing other things

that we think are relevant. We always have some sort of a political bent a topic

BRIAR: [laughs] I can imagine. The person is political.

TOM: We built the show around issues. The show that we did a year ago last October was about lying: truth and lying. There were nine people, including me, in the show, and it was one of my favorite shows. After the show, there was a little party in the lobby of William Way and a woman that I’ve known for a very long time let me know about this festival: Whitman at 200, the celebration of his birth in 1819. She asked me if I would submit a musical theater piece, and I had already been thinking about this. I knew in my research that Oscar had met Oscar Wilde twice in 1882. Wilde came to the United States for the first time when he was 27. He hadn’t really published anything of note, and he was famous for being famous: a celebrity in London. Everyone wanted him at their fancy parties, so he came here on a lecture tour. He started in New York, and then when he got to Philadelphia, which was his second stop, he wanted to see Whitman, who was living in Camden. They brought him over to Whitman’s little row house, and they had a two-hour visit, just the two of them. Then Oscar went off on his tour, and 5 months later, he was passing through Philadelphia again and asked to see Walt again. So, they had another visit. A lot of people have written about those visits, but it’s all speculative because nobody was there but the two of them.

BRIAR: That’s fantastic! I think it’s that whole troupe of “two best friends who live together until they die” [sarcastically] Weren’t they such good best friends? That’s the thing that I’ve seen a lot, mostly between two women: this sort of refusal to acknowledge [queerness]. Of course, we’re speculating now, but it’s so much fun! [laughs]

TOM: I’ve realized early on that they were just going to– even though there was a big age difference Whitman who was in his sixties and Wilde who was in his twenties — immediately relate as two gay men in private. They were closeted even though Oscar was so flamboyant and really a gender-bending presentation of himself. Walt wrote all of that homoerotic poetry, but they didn’t ever say they were gay. It’s like you were saying about two loving roommates…

BRIAR: [Sarcastically] Who are together until death; such great friends! [laughs]

TOM: [laughs] And I realize that within this setting of their privacy that they could talk about anything they wanted, and do whatever they wanted to do. They would go back out into the world and once again not be able to be themselves in the way that they were. For Oscar, I think it was a rare opportunity to be in such an accepting environment. Though their values, their politics, their styles of writing are so different.

BRIAR: I remember reading The Importance of Being Earnest, and in a way, this is bizarre even to conceptualize. I remember reading The Importance of Being Earnest as a begrudging 15-year-old and then landing on Walt Whitman at one point. I think it’s amazing to think about these two writers as even existing in the same temporal space at this meeting that happened– and that these meetings happened is a fact.

TOM: You know Oscar Visits Walt is free? It’s free for undergraduate and graduate students.

BRIAR: Oh, that’s fantastic!

TOM: But we do hope that faculty and staff will come and buy tickets because we do need to sell a few tickets as well.

BRIAR: [laughs] I can imagine why that would be? [laughs] paying creators for their work?! What happened to art for art’s sake? [laughs] Before we leave this space, is there anything you would want to add if you couldn’t leave this room having left anything untouched?

TOM: O My! [laughs]

BRIAR: I know it’s an incredibly nebulous question.

TOM: From me, and my memories of undergraduate life– it was a different world. I came out in a secretive way. I mean, I came out to myself in high school, but I didn’t really do much about it. As an undergrad, I did meet some other gay men, and we were all deeply closeted. There was no mention of homosexuality on campus, certainly no Carriage House, never an article in the paper about it or anything. When I was in graduate school, there were a series of talks in Houston Hall about social issues. Even then, I was pretty closeted, I went. They talked about race, gender challenges, women’s issues, nationality, religion, and homosexuality. Every Wednesday for 6 weeks, these talks happened. I actually went to a few of them because I didn’t want anyone to think that I only chose one. But that had such a big impact on me. There were two speakers Barbara’s Gittings was one of them. She was a member of the library. She was not a trained librarian, but she was part of a group of lesbian and gay librarians who wanted to get queer books into the libraries and available to people. She was a very smart and dynamic leader; she died some years ago but hearing her speak made a big impression on me. Then there was a gay coffee house for a while in Houston Hall one day a week. That would have been in the late 60s, and it was organized by a graduate student. So there was a little bit of gay aspects kind of sneaking around at that time. Now it’s all over the campus and accepted. Probably a few people who are not accepting of it, too…

BRIAR: But they’re in the minority– by in large. I think the university is responding to a degree. You know, I’m thinking of Hedwig and the Angry Inch, which is queer– undeniably queer– and it was one of the most popular shows that our theater group did last year. We sort of reveled in the fact that the producer, the director, the music director, the stage manager: we’re all queer, and we really reveled in that. I was in a class called Queer Communities at the time, and I’m currently in a class called Queer Studies. It’s a class where all we’re talking about is James Baldwin, as a single author studies class.

TOM: I wish I could audit that class!

BRIAR: And the professor– the whole underlining cadence of the class is holding James Baldwin as both a black author and a gay author rather than one or the other, which is how often he is described. So this real intention to sort of like foreground these experiences shows that there is there’s still space for progress, of course, but there is movement towards the direction that it’s headed.

TOM: And you’re here at the time that it’s happening, which is great.

BRIAR: I’m trying to be a part of it! I’m trying to push for change.